Construction contributes between 5% and 10% to national GDP across the Middle East region and growth in this sector is expected to outperform overall regional GDP for several years. Financially backed by booming energy exports, this growth will be driven by regional megatrends including rapid urbanisation, smart city development, the energy transition and economic diversification away from oil and accelerating digital connectivity. Globally, we are forecasted to build more in the next four decades years than the previous four millennia and correspondingly the future looks bright for capital works projects in the region with projects planned or under implementation valued at more than $2.6 trillion. But the sector also delivers, in general, lower profit margins and presents higher risks for stakeholders when compared to other sectors such as technology or healthcare – when compared with finance, telecommunications and manufacturing it also appears under-digitalised and this in itself can limit how much value can be squeezed from data and information. It is widely understood that most construction risk in the infrastructure sector lies in the top 100 m or so of the ground within which most foundations are built. And where atmosphere, lithosphere, biosphere and hydrosphere interact making the shallow subsurface more physically and chemically complex and less predictable than the next 10km – the complex nature of the shallow karstic geology of Qatar or carbonate strata of UAE being examples. With this in mind, we rightly focus on ground risk (that needs to be managed, transferred etc., but not ignored) as part of the overall asset portfolio management program or project risk profile. The historical performance of infrastructure projects provides us with a qualitative indicator of the two components of risk, namely likelihood and consequence. The work of eminent researchers such as Prof. Bent Flyvbjerg of Oxford University’s Saïd Business School and co-workers tells us that, historically, the performance of infrastructure projects has not improved in decades and that most (>90%) of projects do not meet expectations of cost and schedule and, significantly so. This is not to say that construction fails of course, it just doesn’t deliver on initial expectations. So, underperformance compared to initial expectations seems both likely andconsequential – and (according to Flyvbjerg et al.) with larger projects comes greater underperformance so mega- and giga-projects are particularly prone to time and cost overrun. Not all initial project performance expectations are realistic, of course, and some might even be misrepresented. Focussing on geological factors impacting performance we start to think of unforeseen ground conditions that can have a significant impact at the construction stage where the cost of change to a project is very high. But also, earlier, with impact on time and cost a possible tendency towards design conservatism and potentially hidden, wasted cost. And this arising from a lack of reliable site-specific information concerning site variability and the capacity of a foundation design to resist deformation or failure under load. But variability in the state and behaviour of the subsurface is just one problem area in construction risk management. More broadly, when we look at the causes of time and cost overrun, we recognise external factors such as geopolitics and financial market volatility that are beyond project risk management. But also project-specific factors such as unforeseen scope changes, increased project complexity, geology, weather, and other environmental factors…but are these really the fundamental causes of project underperformance in capital works projects?

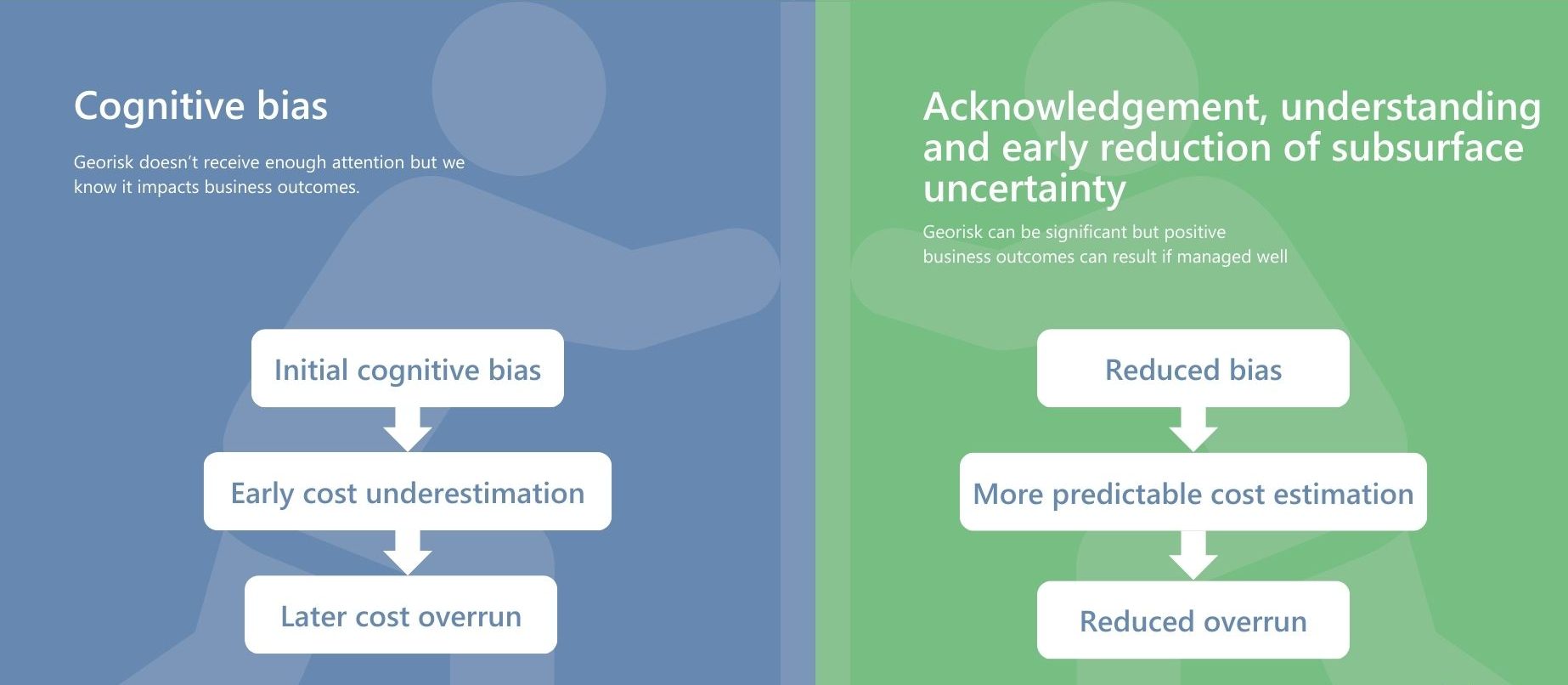

Behavioural science research carried out over the past four decades including Nobel Prize winning insights by behavioural psychologist Daniel Kahneman tells us that cognitive bias or human bias is potentially the key issue in that it distorts our judgement and decision-making – Kahneman’s work summarised in the best-selling book ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’. Human bias appears in several forms and arguably optimism bias is the most readily recognisable (think of how many newly married couples believe that marriage will last forever vs the reality of actual divorce rates). Other key biases include: anchoring bias (how early ideas can disproportionately influence future judgments); confirmation bias (seeking information that confirms preconception); hindsight bias (past events seeming more predictable than they actually were); overconfidence bias (overestimating understanding, capability and ability to predict effectively) and the availability heuristic (relying on recent recallable events rather than a complete and more representative data set). The problem with these biases is that they tend to hard-wire sub-optimal decisions into projects that lead to cost underestimation (or overly optimistic foundations or ground preparation). From that point cost overrun is almost inevitable – just like an astronaut crossing the event horizon of a black hole – there is no way back.

Recalling that most construction risk lies in the ground, how then might we see human bias impacting the management of ground risks and how might we improve the situation?

We already know from projects in the region and also globally that a lack of understanding of the ground can lead to very significant wasted cost and schedule overruns, whether underestimating a risk or overdesigning foundations. And more broadly this can extend to unwanted legal and reputational and other unwanted impacts for organisations. All construction projects will inevitably include some form of final investment decision (FID) that takes into account economic and financial viability, technical feasibility, permitting, licensing and other regulatory risk factors. FID marks the point at which, in general, ground risk starts to be transferred from owners to turnkey contractors and their design teams. But, arguably, ground risk (in the broader family of geo-risks) doesn’t receive sufficient attention in the pre-FID risk profile at an asset portfolio or project scale despite the known unwanted impacts downstream (sub-optimal risk transfer, surprises during construction, adversarial contractual relationships etc). As stated by Paulson (1976)…’although actual expenditures during the early phases of a project are comparatively small, decisions and commitments made during that period have orders of magnitude greater influence on what later expenditures will be’ And ground risk arises from uncertainty and specifically epistemic uncertainty – due to a lack of data, information, knowledge etc. So, we can readily make the link between human bias and ground risk – we simply don’t pay enough attention to ground risk sufficiently early in projects despite knowing, rationally, that there could be significant lost opportunity and unwanted consequences for design and construction and possibly even for asset operations further downstream. Drawing a medical analogy, we see an opportunity for more effective and impactful intervention sufficiently early in the asset cycle, whether it be in a pre-FID in an owner’s risk assessment or post-FID context in an EPC or design-build context.

So, in construction, could we benefit from a paradigm shift or change of approach that addresses human bias? And starting with a greater acknowledgement of the role of subsurface uncertainty as the source of ground risk?

This could then motivate us to understand and then reduce uncertainty leading to better engineering business outcomes. Back to the medical analogy, medical screening has seen great advances in technology over the past few decades (e.g. MRI, CT scans etc.) that has led, demonstrably, to better patient outcomes. We see a similar story in agriculture and improved crop yields. For construction, what might an effective early screening approach look like that could help overcome some of our biased thinking early in the construction cycle?

As an example, owner organisations looking to manage a portfolio of land assets prior to individual project development might undertake multi-factor site ranking and selection as part of the process to FID – budgets are driven by investor risk appetite and expectations of return. Schedule is often very constrained and therefore (ideally) subsurface information would need to be acquired cost-effectively with little or no permitting or regulatory requirements, meaning light-footprint field operations and over limited time windows with minimal social and environmental impact. Also, robust results would be required in time to impact rational decision making so this necessitates rapid delivery of insights for decision-makers. Conventional means of obtaining subsurface insights generally rely on direct sampling and logging with boreholes and probings and both in situ and lab-based testing. Collectively, these activities have been the traditional mainstay of geotechnical engineering and continue to serve the industry very well, but they rely on heavy assets requiring extended timelines, and with extended timelines comes more risk. Also, when visualising the subsurface in 2D or 3D as a ground model built from localised measurements, much of the model space is left empty, to be filled with some form of interpolation, extrapolation and modelling judgement – and possibly hidden risks. But in this context a paradigm shift is possible. Firstly we have seen significant developments in geophysical technologies that allow us to scale established 3D screening approaches from regional to engineering site scales; secondly we are in an age of miniaturised sensors – a geophysical sensor can now be smaller and lighter that a fizzy drink can and hundreds to thousands of sensors can be placed at a site by a small field crew in a single day; thirdly, memory technology is such that sensors can be left for days or weeks recording vast quantities of useful, dense, subsurface data; fourthly, we now have access to cloud technologies that mean unparalleled computing power to process these enormous data sets with very high data density filling the model space – as an example – 1000 sensors over a project footprint can deliver almost one million data points that are reconciled into a 3D ground model of geotechnical properties – significantly more dense and spatially representative than from relatively few conventional data; fifthly the development of AI and related disciplines such as machine learning mean that we can better reconcile the different data inputs from advanced 2D and 3D screening, conventional 1D geotechnical investigation and performance testing to create a more representative ground model. All of this to inform decision-making for site ranking and selection, fatal flaw analyses, site layout optioneering, effective risk transfer mechanisms and informing other pre-FID themes. And critically a model that can be accessed and visualised by specialists and non-specialists alike. Of course, the same overall screening approach applies post-FID for the EPC or design-builder, who, frequently with a fixed budget and schedule, will be interested in avoiding surprises during construction but also in delivering an effective design based on better site-specific information with shorter timelines and fewer assumptions, effectively customized ground intelligence, to help them better manage their delivery risk into profit. A better ground model conveys confidence to planners, designers, and constructors that the ground has been characterised well.

While we might need to accept that human bias is an issue in construction projects in the region and more widely, there is a means to mitigate such bias through acknowledgement, understanding and then early reduction of subsurface uncertainty. Advanced screening, effectively doing the right things, well, and at the right time, can reduce such uncertainty, enabling more effective and less-biased data-driven decision-making and informing more thorough and rational ground risk assessments during planning and execution. According to McKinsey & Co., organisations that address bias tend to generate improved business outcomes – shifting the paradigm in ground risk management to improve early decision-making should therefore make good business sense for the construction sector.