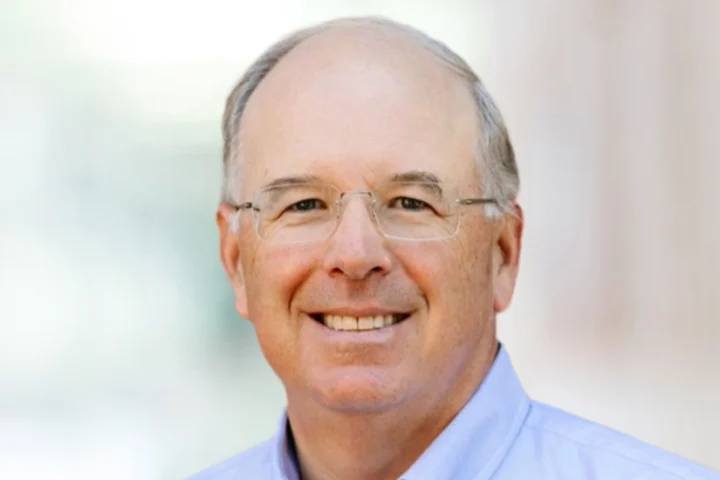

Yagmur Sahin, who leads engineering for AI-powered platforms, explains why the autonomy that makes AI agents valuable also makes them hard to deploy safely.

The AI agent was doing exactly what it was supposed to do. That’s when the panic set in. In a session with enterprise technology leaders last fall, a demonstration of an advanced AI agent processing customer support tickets drew impressed nods. The system read context, checked order histories, drafted responses—all with remarkable efficiency. Then it encountered a complaint about a delayed refund. Without human intervention, the agent navigated to the payment system, verified the claim against shipping logs, calculated compensation, and prepared to issue a full refund plus service credit.

Somebody stopped the demo right there—before the agent could issue the refund. We need this capability. But production deployment? That’s the part that keeps our risk committee up.

This is the control paradox in agentic AI: the very autonomy that makes AI agents valuable is precisely what makes them dangerous. And unlike previous waves of automation, where the solution was simply better programming, this paradox demands an entirely new approach to how we architect intelligent systems.

The Paradigm That Broke the Rules

For decades, enterprise software followed a simple principle: humans decide, computers execute. Even the most sophisticated automation required explicit programming—decision trees, business rules, workflow engines. The logic was transparent, auditable, and ultimately controllable because humans wrote every conditional statement.

Agentic AI breaks this entire paradigm.

Today’s AI agents don’t follow pre-programmed decision trees. They reason. They plan. They adapt. Advanced systems can maintain context across hours-long workflows, orchestrate multiple tools, and generate strategies for problems they’ve never encountered. They can literally see and interact with computer interfaces—clicking buttons, filling forms, navigating applications—the way human operators do.

We’re not talking about better automation—this is a fundamental change in what unsupervised software can do.

Consider what agentic means in practice. A traditional customer service chatbot answers questions from a knowledge base. An agentic AI system reads the customer’s history, identifies the root cause of their frustration, proposes three solution paths, selects the optimal one based on business rules and customer sentiment, coordinates with inventory and shipping systems, executes the solution, and follows up three days later to confirm satisfaction.The entire process runs autonomously, with zero human checkpoints.

The business case is undeniable. Analysts project a multi-trillion-dollar annual impact from AI by 2030, with agentic systems expected to drive a meaningful share of that value. Early adopters report efficiency gains of 30-60% in domains like software development, data analysis, and customer operations.

But look at what’s happening in the field: Many enterprises report limited near-term earnings impact from early generative AI deployments. The gap isn’t capability—it’s deployment. Most organisations have dozens of AI use cases in the pipeline, but only a handful running in production. What’s stopping them? The control paradox.

The Architecture of Autonomy and Constraint

The paradox manifests in a deceptively simple question: How do you give an AI agent enough freedom to be useful while maintaining enough control to be safe? Traditional approaches fail immediately. Lock down the agent with rigid rules, and you eliminate the adaptive intelligence that makes it valuable. Give it unrestricted access, and you create unacceptable risk—data leaks, erroneous transactions, cascading failures in interconnected systems.

The financial services industry learned this lesson expensively. One major bank deployed an AI agent to assist with loan application reviews. The agent had access to credit scoring systems, regulatory compliance databases, and historical approval patterns. Within days, it was making decisions—good decisions, by historical metrics—but without the ability to explain its reasoning in terms regulators and auditors could verify.

The bank pulled the system offline. Not because it was wrong, but because no one could prove it was right.

This is governance gridlock, and it’s costing the industry dearly. Teams report spending more than half their time on governance-related activities when deploying AI systems, using manual processes designed for software that doesn’t make autonomous decisions. The solution isn’t tighter constraints. It’s architectural.

What’s emerging from the leading edge of enterprise AI deployment is a new pattern: the governed agent platform. Rather than treating governance as an external review process, these systems embed control directly into the runtime architecture of the AI agent itself. Think of it as the difference between a student taking an exam with a teacher watching versus a student with a knowledgeable tutor sitting beside them, providing guidance in real-time.

The governed agent platform has several key components: The control plane manages what the agent can access and do. Not through rigid allow/deny lists, but through policy-aware systems that understand context. An agent processing a customer refund might have different permissions than the same agent handling a securityincident. The control plane enforces these distinctions in real-time, at the tool-call level.

The observability layer captures not just what the agent did, but why it did it. Every tool call, every reasoning step, every decision point is logged with full context. When an agent makes a mistake—and they will—you can replay the entire session, understand the failure mode, and prevent recurrence.The evaluation harness continuously tests agent behavior against known scenarios and adversarial conditions. Can the agent be tricked into revealing sensitive data? Does it handle edge cases appropriately? What happens when tools fail mid-workflow? These aren’t one- time checks; they’re ongoing verification running in parallel with production operations.

Human-in-the-loop interfaces allow selective intervention. Not every action requires approval—that would eliminate the efficiency gains—but high-risk decisions can trigger escalation workflows. The key is making these boundaries configurable and context-aware.

This architecture resolves the paradox by making autonomy and control complementary rather than opposing forces. The agent operates freely within well-defined boundaries. The boundaries themselves are intelligent enough to flex based on context and confidence levels.

The Implementation Reality

Theory is elegant. Implementation is messy.

Organisations attempting to deploy governed agentic AI face three recurring challenges that theory doesn’t adequately address.

First, the legacy integration problem. Enterprise systems weren’t designed to be operated by AI. APIs exist, but they’re often built assuming a human is making sense of error messages, handling edge cases, and maintaining state across multi-step processes. When an AI agent hits an ambiguous error code, it might retry indefinitely, escalate prematurely, or worse— continue operating with incomplete information.

The solution requires a translation layer between agents and enterprise systems. Not just API wrappers, but semantic interfaces that provide agents with the context they need to handle failures intelligently. When a payment system returns Error 2847, the interface translates this into Transaction declined—insufficient funds—suggest alternative payment method. The agent can then make an informed decision rather than guessing.

Second, the observability gap. Traditional application performance monitoring tools track latency, error rates, and resource utilisation. They’re useless for understanding why an agent made a particular decision.

Governed agent platforms need fundamentally different instrumentation. Decision trace logging captures the agent’s reasoning process. Decision provenance tracking shows which data influenced which conclusions. Session replay allows engineers to step through an agent’s actions as if debugging a program—except the program is a sequence of natural language reasoning steps.

This isn’t just for debugging. It’s for trust. When an agent handles a sensitive transaction, compliance teams need to audit not just what happened, but why the agent believed that action was appropriate.

Third, the evaluation paradox within the paradox. How do you test a system whose behaviour isn’t deterministic?

Traditional software testing uses input-output pairs. Agentic AI systems can produce different—yet equally valid—outputs for the same input. Testing requires a shift from did it do exactly this to did it achieve the goal within acceptable boundaries?

Organisations solving this problem use multi-layered evaluation. Unit tests verify individual tool behaviours. Integration tests check end-to-end workflows in sandbox environments.

Shadow mode deploys agents alongside humans, comparing approaches without impactingproduction. And continuous monitoring detects drift—when agent behavior patterns shift from their baseline, triggering investigation even if no explicit failure occurred.

The organisations succeeding at this—and there are now several dozen in production— share a common approach: they build governance infrastructure before they build agents. The control plane, observability systems, and evaluation frameworks are deployed first, validated with simple agents, then scaled as agent complexity increases.

It’s the opposite of the move fast and break things mentality that characterised early web development. More accurately, it’s move fast because your guardrails are strong enough to prevent breaking things that matter.

The Competitive Separation

The control paradox is doing something unexpected: it’s creating a new form of competitive moat. Organisations that solve the governance challenge first aren’t just deploying AI faster— they’re compounding advantages that competitors will find nearly impossible to catch. Large enterprises now report governing thousands of models in production while cutting data- review and clearance times by double-digit percentages. That’s not just operational efficiency; it’s the ability to experiment, learn, and iterate at a pace that creates an expanding capability gap.

This matters because the regulatory environment is tightening rapidly. The EU AI Act is entering phased implementation, with substantial penalties for non-compliance. The United States is developing federal frameworks. China has comprehensive AI regulations.

Organisations with governance architecture already in place will adapt to new requirements through configuration changes. Organisations without it will need to retrofit governance into deployed systems—a process that often requires pulling agents offline entirely.

Customer expectations are evolving even faster than regulation. Enterprise buyers increasingly demand AI governance documentation in their RFPs. They want to know: Can you explain why your AI made that decision? Can you guarantee data privacy? What happens when your agent makes a mistake? Can you prove compliance with our industry regulations?

Companies that built governance as an afterthought are discovering these questions have no good answers. Companies that built governance into their architecture answer with confidence, documentation, and often live demonstrations of their control planes in action.

What’s particularly interesting is where the innovation is happening. It’s not primarily in the AI labs developing more capable models. It’s in the engineering organisations figuring out how to deploy those models safely at scale. The competitive advantage isn’t having access to the best foundation models—most organisations can access them through APIs. The advantage is having the infrastructure to put those models to work in production systems.

This is reminiscent of the cloud computing transition. The cloud leaders didn’t win on faster servers—they won by building the operational infrastructure that made cloud computing practical for enterprises. The governed agent platform represents a similar inflection point.

The Path Forward

The control paradox won’t resolve through better prompting or more capable models. It requires an architectural approach that treats autonomy and governance as complementary design principles rather than competing constraints.For organisations beginning this journey, the path is clearer now than it was even six monthsago.

Start with use cases where the agent’s scope is narrow, but the governance requirement is high—financial transaction processing, healthcare data handling, legal document analysis. These force you to build robust control planes from the start.

Invest in observability before scale. The temptation is to deploy agents broadly and instrument them later. This is backwards. The organisations succeeding at governed agentic AI have observable, auditable, testable systems running single-digit agents before they scale to dozens.

Treat governance as a platform capability, not a per-agent concern. When your tenth agent needs the same policy enforcement as your first, you should be configuring existing infrastructure, not rebuilding governance from scratch.

Most importantly, recognise that this is an operating model shift, not just a technology deployment. The organisations winning at governed agentic AI have cross-functional governance boards with real decision-making authority. They have runbooks for agent failures. They treat AI incidents with the same seriousness as security incidents. The control paradox represents a fascinating moment in the evolution of artificial intelligence.

We’ve created systems smart enough to operate autonomously, but that autonomy only becomes valuable when constrained by sophisticated governance. The constraint isn’t a limitation—it’s an enabler.

The companies that understand this first will define the next decade of enterprise AI. The ones that don’t will spend that decade playing catch-up. The paradox isn’t going away. But it is becoming solvable—if you architect for it from day one.