In the last few months of 2017, security companies made their own forecasts about incoming cyberthreats and the measures that needed to be taken to ensure a better and cybersafer 2018, often advocating the use of protective software tools made by that vendor. Lo and behold! 2018 started with a scenario hardly anyone could have foreseen. Two serious design vulnerabilities in CPUs were exposed that make it possible, although not always that easy, to steal sensitive, private information such as passwords, photos, perhaps even cryptography certificates.

Lots has been written about these vulnerabilities already: if you are new to the subject we suggest that you read Aryeh Goretsky’s article “Meltdown and Spectre CPU Vulnerabilities: What You Need to Know.”

Now, there is a much larger underlying issue. Yes, software bugs happen, hardware bugs happen. The first are usually fixed by patching the software; in most cases the latter are fixed by updating the firmware. However, that is not possible with these two vulnerabilities as they are caused by a design flaw in the hardware architecture, only fixable by replacing the actual hardware.

Luckily, with cooperation between the suppliers of modern operating systems and the hardware vendors responsible for the affected CPUs, the Operating Systems can be patched, and complemented if necessary with additional firmware updates for the hardware. Additional defensive layers preventing malicious code from exploiting the holes – or at least making it much harder – are an “easy” way to make your desktop, laptop, tablet and smartphone devices (more) secure. Sometimes this happens at the penalty of a slowdown in device performance, but there’s more to security than obscurity and sometimes you just have to suck it up and live with the performance penalty. To be secure, the only other option is either to replace the faulty hardware (in this case, there is no replacement yet) or to disconnect the device from the network, never to connect it again (nowadays not desirable or practical).

And that is exactly where the problems begin. CPUs made by AMD, ARM, Intel, and probably others are affected by these vulnerabilities: specifically, ARM CPUs are used in a lot of IoT devices, and those are devices that everybody has, but they forget they have them once they are operating, and this leaves a giant gap for cybercriminals to exploit. According to ARM, they are already “securing” a Trillion (1,000,000,000,000) devices. Granted, not all ARM CPUs are affected, but if even 0.1% of them are, it still means a Billion (1,000,000,000) affected devices.

Now I can hear already someone say “What kind of sensitive data can be stolen from my Wi-Fi-controlled light? Or my refrigerator? Or from my digital photo frame? Or from my Smart TV?” The answer is simple: lots. Think about your Wi-Fi password (which would make it possible for anyone to get onto your local network), your photos (luckily you only put the decent photos on the digital photo frame in your living room, right? Or did you configure it to connect automatically to Instagram or DropBox to fetch your newly-taken pictures?), your credentials to Netflix? Your… Eh… There is a lot of information people nowadays store on IoT devices.

Ok, to be fair, to get access to these IoT devices, your attackers need to have compromised the network already to get into them? Or they have to compromise the supply chain, or compromise apps or widgets that can run on the device, or… There are many ways to get access to these devices.

It is not feasible, in fact not even possible, to replace all CPUs in all devices. It would be too costly, besides the success rate for unsoldering and resoldering pin-throughs in multi-layer boards will never be 100%. In the real world, people will keep their existing devices until those devices reach the end of their lifecycles. So for years to come, people will have households with vulnerable devices.

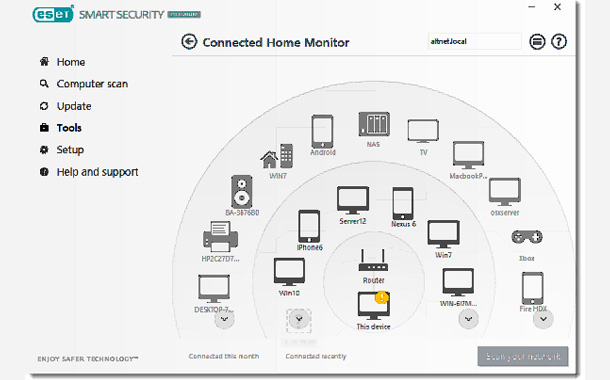

Do you know how many IoT devices you have on your local network? Probably not. There may even be some devices you have never realized are there in your household at all. Why not try ESET Internet Security or ESET Smart Security, with the updated Connected Home Monitor, which will help you identify all the network-aware devices in your network, and in many cases can identify vulnerabilities in those devices. It will also alert you when a device not previously seen is connecting to your network.

As mentioned, it would be too costly to replace all the faulty CPUs, especially in the cheaper IoT devices. On those, even updating the firmware or (patching) the operating system may not be possible. As a warning, when you are buying a new IoT device, it makes sense to check which CPU it is running on, and if that CPU is affected by these vulnerabilities. It is expected that some devices may suddenly be offered cheaply by the manufacturer, hoping to rid their inventory of old(er) faulty CPUs while manufacturing new devices with updated CPUs, when these become available. So: caveat emptor. A bargain may turn out to be a nightmare once you connect it to your network.

The bottom-line: IoT or “smart” devices are here to stay, affected or not, so be sensible with the information you store within them.