The banking Trojan dubbed Fakecalls masquerades as a banking app and mimics the telephone customer support of the most popular South Korean banks. Unlike regular banking Trojans, it can discreetly intercept calls to real banks using their own connection. Under the guise of bank employees, the cybercriminals try to coax payment data or other confidential information out of the victim.

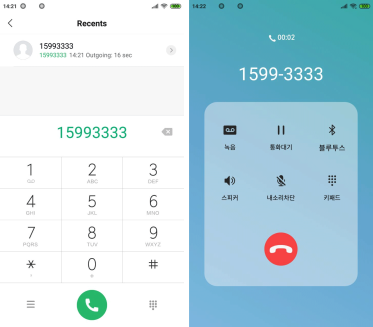

Kaspersky researchers uncovered the Fakecalls’ banking Trojan in January 2021. During their investigation they found that when a victim calls the bank’s hotline the Trojan opens its own fake screen call in place of the bank’s authentic one. There are two possible scenarios that unfold after the call is intercepted. In the first, Fakecalls connects the victim directly with cybercriminals who present themselves as the banks’ customer support. In the alternative scenario, the Trojan plays prerecorded audio that imitates a standard greeting from the bank and mimics a standard conversation using an automated voicemail.

From time to time, the Trojan inserts small audio snippets in Korean. For example, “Hello. Thank you for calling our bank. Our call center is currently receiving an unusually large volume of calls. A consultant will speak with you as soon as possible.” This enables cybercriminals to gain the trust of their victims by making them believe that the call is real. The main objective of such calls is to coax as much vulnerable information, including bank account details, from their victims as possible.

However, cybercriminals using this Trojan have failed to consider that some of their potential victims may use different interface languages, for example, English instead of Korean. The Fakecall screen only has a Korean version, which means some of the users using the English interface language will smell a rat and uncover the threat.

When downloaded, the Fakecall app, disguised as an authentic banking app, asks for a variety of permissions, such as access to contacts, microphone, camera, geolocation and call handling. These permissions allow the Trojan to drop incoming calls and delete them from the device’s history, for instance, when the real bank is trying to reach its client. The Fakecalls’ Trojan is not only able to control incoming calls but is also able to spoof outgoing calls. If cybercriminals want to contact the victim, the Trojan displays its own call screen over the system’s one. As a result, the user does not see the real number used by the cybercriminals but the phone number of the bank’s support service shown by the Trojan.

As fraudsters are trying to convince the victim that the app is real, Fakecalls completely mimic the mobile apps of well-known South Korean banks. They insert the real bank logos and display the real support numbers of the banks as displayed on the main page of their official websites.

“Banking clients are constantly told to be aware of calls from scammers. However, when they are directly trying to reach bank customer support themselves, they do not expect any danger. Generally speaking, we trust bank employees – we call them for help and, therefore, we may tell them, or their impersonators, any requested information. The cybercriminals who created Fakecalls have combined two dangerous technologies: banking Trojans and social engineering, so their victims are more likely to lose money and personal data. When downloading a new mobile banking app, take into consideration what permissions it asks for. If it’s trying to get suspiciously excessive access to device controls, including call handling access, then it is most likely that the app is a banking Trojan,” comments Igor Golovin, security researcher at Kaspersky.